Culture of Europe

The culture of Europe is diverse, and rooted in its art, architecture, traditions, cuisines, music, folklore, embroidery, film, literature, economics, philosophy and religious customs.[1]

Definition

[edit]

Whilst there are a great number of perspectives that can be taken on the subject, it is impossible to form a single, all-embracing concept of European culture.[2] Nonetheless, there are core elements which are generally agreed upon as forming the cultural foundation of modern Europe.[3] One list of these elements given by K. Bochmann includes:[4]

- A common cultural and spiritual heritage derived from Greco-Roman antiquity, Christianity, Judaism, the Renaissance, its Humanism, the political thinking of the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and the developments of Modernity, including all types of socialism;[5][4]

- A rich and dynamic material culture, parts of which have been extended to the other continents as the result of industrialization and colonialism during the "Great Divergence";[5]

- A specific conception of the individual expressed by the existence of, and respect for, a legality that guarantees human rights and the liberty of the individual;[5]

- A plurality of states with different political orders, which share new ideas with one another.[5]

- Respect for peoples, states, and nations outside Europe.[5]

Berting says that these points fit with "Europe's most positive realizations".[6] The concept of European culture is arguably linked to the classical definition of the Western world. In this definition, Western culture is the set of literary, scientific, political, artistic, and philosophical principles which set it apart from other civilizations. Much of this set of traditions and knowledge is collected in the Western canon.[7] The term has come to apply to countries whose history has been strongly marked by European immigration or settlement during the 18th and 19th centuries, such as the Americas, and Australasia, and is not restricted to Europe.

The Nobel Prize laureate in Literature Thomas Stearns Eliot, in his 1948 book Notes Towards the Definition of Culture, credited the prominent Christian influence upon the European culture:[8] "It is in Christianity that our arts have developed; it is in Christianity that the laws of Europe have--until recently--been rooted."

History

[edit]In the 5th century BCE, Greek philosopher Herodotus conceptualized what it was that divided Europe and Asia, differentiating Europe, as the West (where the sun sets), from the East (where the sun rises).[9][10][11] A later concept of Europe as a cultural sphere emerged during the Carolingian Renaissance of the late 8th and early 9th century, limited to the territories of Europe that practiced Western Christianity at the time.[12]

Europe underwent social change and transition from the Middle Ages to modernisation, when the cultural movement Renaissance, from the 15th to 16th century, spread values and art techniques across the continent.

Art

[edit]

Prehistoric art

[edit]Surviving European prehistoric art mainly comprises sculpture and rock art. It includes the oldest known representation of the human body, the Venus of Hohle Fel, dating from 40,000 to 35,000 BC, found in Schelklingen, Germany, and the Löwenmensch figurine, from about 30,000 BC, the oldest undisputed piece of figurative art. The Swimming Reindeer of about 11,000 BCE is among the finest Magdalenian carvings in bone or antler of animals in the art of the Upper Paleolithic. At the beginning of the Mesolithic in Europe, the figurative sculpture was greatly reduced, and remained a less common element in art than relief decoration of practical objects until the Roman period, despite some works such as the Gundestrup cauldron from the European Iron Age and the Bronze Age Trundholm sun chariot. The oldest European cave art dates back to 40,800[clarification needed] and can be found in the El Castillo Cave in Spain, but cave art exists across the continent. Rock painting was also performed on cliff faces, but fewer of those paintings have survived because of erosion. One well-known example is the rock paintings of Astuvansalmi in the Saimaa area of Finland.

The Rock Art of the Iberian Mediterranean Basin forms a distinct group with the human figure the main focus, often seen in large groups, with battles, dancing, and hunting all represented, as well as other activities and details such as clothing. The figures are generally rather sketchily depicted in thin paint, with the relationships between the groups of humans and animals more carefully depicted than individual figures. Prehistoric Celtic art is another distinct grouping from much of Iron Age Europe and survives mainly in the form of high-status metalwork skillfully decorated with complex, elegant, and mostly abstract designs, often using curving and spiral forms. Full-length human figures of any size are so rare that their absence may represent a religious taboo. As the Romans conquered Celtic territories, the style vanished, except in the British Isles, where it influenced the Insular style of the Early Middle Ages.

Classical art

[edit]

Ancient Greek art stands out among that of other ancient cultures for its development of naturalistic but idealized depictions of the human body, in which largely nude male figures were generally the focus of innovation. The rate of stylistic development between about 750 and 300 BC was remarkable by ancient standards, and in surviving works is best seen in Ancient Greek sculpture. There were important innovations in painting, which have to be essentially reconstructed due to the lack of original survivals of quality, other than the distinct field of painted pottery. Black-figure pottery and the subsequent red-figure pottery are famous and influential examples of the Ancient Greek decorative arts.

Roman art was influenced by Greece and can in part be taken as a descendant of ancient Greek painting and sculpture, but was also strongly influenced by the more local Etruscan art of Italy. The sculpture was perhaps considered as the highest form of art by Romans, but figure painting was also very highly regarded. The Roman sculpture is primarily portraiture derived from the upper classes of society as well as depictions of the gods. However, Roman painting does have important unique characteristics. Among surviving Roman paintings are wall paintings, many from villas in Campania, in Southern Italy, especially at Pompeii and Herculaneum. Such painting can be grouped into four main "styles" or periods and may contain the first examples of trompe-l'œil, pseudo-perspective, and pure landscape. Early Christian art grew out of Roman popular, and later Imperial, art and adapted its iconography from these sources.

Medieval art

[edit]Medieval art can be broadly categorized into the Byzantine art of the Eastern Roman Empire, and the Gothic art that emerged in Western Europe over the same period.

Byzantine art was strongly influenced by its classical heritage but distinguished itself by the development of a new, abstract, aesthetic, marked by anti-naturalism and a favor for symbolism. The subject matter of monumental Byzantine art was primarily religious and imperial: the two themes are often combined, as in the portraits of later Byzantine emperors that decorated the interior of the sixth-century church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. However, the Byzantines inherited the Early Christian distrust of monumental sculpture in religious art, and produced only reliefs, of which very few survivals are anything like life-size, in sharp contrast to the medieval art of the West, where monumental sculpture revived from Carolingian art onwards. Small ivories were also mostly in relief. The so-called "minor arts" were very important in Byzantine art, and luxury items, including ivories carved in relief as formal presentation Consular diptychs or caskets such as the Veroli casket, hardstone carvings, enamels, glass, jewelry, metalwork, and figured silks were produced in large quantities throughout the Byzantine era.

Migration Period art includes the art of the Germanic tribes on the continent, as well the start of the distinct Insular art or Hiberno-Saxon art of the Anglo-Saxon and Celtic fusion in the British Isles. It covers many different styles of art including the polychrome style and the Scythian and Germanic animal style. After Christianization, Migration Period art developed into various schools of Early Medieval art in Western Europe, which are normally classified by region, such as Anglo-Saxon art and Carolingian art, before the continent-wide styles of Romanesque art and finally Gothic art developed.

Romanesque art and Gothic art dominated Western and Central Europe from approximately 1000 AD to the rise of the Renaissance style in the 15th century or later, depending on the region. The Romanesque style was greatly influenced by Byzantine and Insular art. Religious art, such as church sculpture and decorated manuscripts, was particularly prominent. Art of the period was characterized by a very vigorous style in both sculpture and painting. Colors tended to be very striking and mostly primary. Compositions usually had little depth, and needed to be flexible to be squeezed into the shapes of historiated initials, column capitals, and church tympanums. Figures often varied in size in relation to their importance, and landscape backgrounds, if attempted at all, were closer to abstract decorations than realism.

Gothic art developed from Romanesque art in Northern France in the 12th century AD, led by the concurrent development of Gothic architecture. It spread to all of Western Europe, and much of Southern and Central Europe. In the late 14th century, the sophisticated court style of International Gothic developed, which continued to evolve until the late 15th century. In many areas, especially England and Germany, Late Gothic art continued well into the 16th century. Gothic art was often typological in nature, showing the stories of the New Testament and the Old Testament side by side. Saints' lives were often depicted. Images of the Virgin Mary changed from the Byzantine iconic form to a more human and affectionate mother, often showing the refined manners of a courtly lady.

Secular art came into its own during the gothic period alongside the creation of a bourgeois class who could afford to patronize the arts and commission works. Increased literacy and a growing body of secular vernacular literature encouraged the representation of secular themes in art. With the growth of cities, trade guilds were formed, and artists were often required to be members of a painters' guild—as a result, because of better record-keeping, more artists are known to us by name in this period than any previous.

Renaissance art

[edit]Renaissance art emerged as a distinct style in northern Italy from around 1420, in parallel with developments which occurred in philosophy, literature, music, and science. It took as its foundation the art of Classical antiquity, but was also influenced by the art of Northern Europe and contemporary scientific knowledge. Renaissance artists painted a wide variety of themes. Religious altarpieces, fresco cycles, and small works for private devotion were very popular. Painters in both Italy and northern Europe frequently turned to Jacobus de Voragine's Golden Legend (1260), a highly influential sourcebook for the lives of saints that had already had a strong influence on Medieval artists. Interest in classical antiquity and Renaissance humanism also resulted in many Mythological and history paintings. Decorative ornament, often used in painted architectural elements, was especially influenced by classical Roman motifs.

Techniques characteristic of Renaissance art include the use of proportion and linear perspective; foreshortening, to create an illusion of depth; sfumato, a technique of softening of sharp outlines by subtle blending of tones to give the illusion of depth or three-dimensionality; and chiaroscuro, the effect of using a strong contrast between light and dark to give the illusion of depth or three-dimensionality.

Mannerism, Baroque and Rococo

[edit]Renaissance Classicism spawned two different movements—Mannerism and the Baroque. Mannerism, a reaction against the idealist perfection of Classicism, employed distortion of light and spatial frameworks in order to emphasize the emotional content of a painting and the emotions of the painter. Where High Renaissance art emphasizes proportion, balance, and ideal beauty, Mannerism exaggerates such qualities, often resulting in compositions that are asymmetrical or unnaturally elegant. The style is notable for its intellectual sophistication as well as its artificial (as opposed to naturalistic) qualities. It favors compositional tension and instability rather than the balance and clarity of earlier Renaissance paintings.

In contrast, Baroque art took the representationalism of the Renaissance to new heights, emphasizing detail, movement, lighting, and drama. Perhaps the best-known Baroque painters are Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Peter Paul Rubens, and Diego Velázquez. Baroque art is often seen as part of the Counter-Reformation— the revival of spiritual life in the Roman Catholic Church. Religious and political themes are widely explored within the Baroque artistic context, and both paintings and sculptures are characterized by a strong element of drama, emotion, and theatricality. Baroque art was particularly ornate and elaborate in nature, often using rich, warm colors with dark undertones. Dutch Golden Age painting is a distinct subset of Baroque, leading to the development of secular genres such as still life, genre paintings of everyday scenes, and landscape painting.

By the 18th century, Baroque art had developed into Rococo in France. Rococo art was even more elaborate than the Baroque, but it was less serious and more playful. The artistic movement no longer placed emphasis on politics and religion, focusing instead on lighter themes such as romance, celebration, and appreciation of nature. Furthermore, it sought inspiration from the artistic forms and ornamentation of Far Eastern Asia, resulting in the rise in favor of porcelain figurines and chinoiserie in general. Rococo soon fell out of favor, being seen by many as a gaudy and superficial movement emphasizing aesthetics over meaning.

Neoclassical, Romanticism, and Realism

[edit]

Neoclassicism began in the 18th century as a counter-movement opposing Rococo. It desired for a return to the simplicity, order, and 'purism' of classical antiquity, especially ancient Greece and Rome. Neoclassicism was the artistic component of the intellectual movement known as the Enlightenment. Neoclassicism had become widespread in Europe throughout the 18th century, especially in the United Kingdom. In many ways, Neoclassicism can be seen as a political movement as well as an artistic and cultural one. Neoclassical art places emphasis on order, symmetry, and classical simplicity; common themes in Neoclassical art include courage and war, as were commonly explored in ancient Greek and Roman art. Ingres, Canova, and Jacques-Louis David are among the best-known neoclassicists.

Just as Mannerism rejected Classicism, Romanticism rejected the aesthetic of the Neoclassicists, specifically the highly objective and ordered nature of Neoclassicism, favoring instead a more individual and emotional approach to the arts. Emphasis was placed on nature, especially when aiming to portray the power and beauty of the natural world, and emotions. Romantic art often used colors in order to express feelings and emotions. Romantic art was inspired by ancient Greek and Roman art and mythology, but also takes much of its aesthetic qualities from medievalism and Gothicism, as well as later mythology and folklore. Among the greatest Romantic artists were Eugène Delacroix, Francisco Goya, J. M. W. Turner, John Constable, Caspar David Friedrich, and William Blake.

In response to these changes caused by Industrialisation, the movement of Realism emerged, which sought to accurately portray the conditions and hardships of the poor in the hopes of changing society. In contrast with Romanticism, which was essentially optimistic about mankind, Realism offered a stark vision of poverty and despair. While Romanticism glorified nature, Realism portrayed life in the depths of an urban wasteland. Like Romanticism, Realism was a literary as well as an artistic movement. Other contemporary movements were more Historicist in nature, such as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which attempted to return art to its state of "purity" prior to Raphael, and the Arts and Crafts Movement, which reacted against the impersonality of mass-produced goods and advocated a return to medieval craftsmanship.

Music

[edit]Classical music

[edit]Pre-1600

[edit]This broad era encompasses early music, which generally comprises Medieval music (500–1400) and Renaissance music (1400–1600), but sometimes includes Baroque music (1600–1760).

Post-1600

[edit]This era includes the common practice period from approximately 1600 to 1900, as well as the modernist and postmodernist styles that emerged after 1900 and which continue to the present day.

Modern music

[edit]Folk music: Europe has a wide and diverse range of indigenous music, sharing common features in rural, traveling, or maritime communities. Folk music is embedded in an unwritten, oral tradition, but was increasingly transcribed from the nineteenth century onwards. Many classical composers used folk melodies, and folk music continues to influence popular music in Europe, however its prominence varies across countries. See the list of European folk music.

Popular music: Europe has imported many different genres of popular music, including Rock, Blues, R&B Soul, Jazz, Hip-Hop and Pop. Various modern genres named after Europe are rooted in Electronic dance music (EDM), and include Europop, Eurodisco, Eurodance and Eurobeat. Popular music can vary considerably across Europe. Styles of music from nations formerly under Ottoman rule enrich this variation, with their native musical traditions having fused with Ottoman musical influences over centuries.

Media

[edit]Television

[edit]Radio

[edit]Newspapers

[edit]Architecture

[edit]

Prehistoric architecture

[edit]The Neolithic long house was a long, narrow timber dwelling built by the first farmers in Europe beginning at least as early as the period 5000 to 6000 BC. Knap of Howar and Skara Brae, the Orkney Islands, Scotland, are stone-built Neolithic settlements dating from 3,500 BC. Megaliths found in Europe and the Mediterranean were also erected in the Neolithic period. See Neolithic architecture.

Ancient classical architecture

[edit]Ancient Greek architecture was produced by the Greek-speaking people whose culture flourished on the Greek mainland, the Peloponnese, the Aegean Islands, and in colonies in Anatolia and Italy for a period from about 900 BC until the 1st century AD. Ancient Greek architecture is distinguished by its highly formalized characteristics, both of structure and decoration. The formal vocabulary of ancient Greek architecture, in particular the division of architectural style into three defined orders: the Doric Order, the Ionic Order, and the Corinthian Order, was to have a profound effect on the Western architecture of later periods.

Ancient Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but differed from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural style. The two styles are often considered one body of classical architecture. Roman architecture flourished in the Roman Republic and even more so under the Empire, when the great majority of surviving buildings were constructed. It used new materials, particularly concrete, and newer technologies such as the arch and the dome to make buildings that were typically strong and well-engineered. Large numbers remain in some form across the empire, sometimes complete and still in use.]

Medieval architecture

[edit]

Romanesque architecture combines features of ancient Roman and Byzantine buildings and other local traditions. It is known for its massive quality, thick walls, round arches, sturdy pillars, groin vaults, large towers, and decorative arcading. Each building has clearly defined forms, frequently of a very regular, symmetrical plan; the overall appearance is one of simplicity when compared with the Gothic buildings that were to follow. The style can be identified right across Europe, despite regional characteristics and different materials, and is most frequently seen in churches. Plenty of examples of this architecture are found alongside the Camino de Santiago.

Gothic architecture flourished in Europe during the High and Late Middle Ages. It evolved from Romanesque architecture and was succeeded by Renaissance architecture. Originating in 12th century France and lasting into the 16th century, Gothic architecture was known during the period as Opus Francigenum ("French work"), with the term Gothic first appearing during the latter part of the Renaissance. Its characteristics include the pointed arch, the ribbed vault (which evolved from the joint vaulting of Romanesque architecture), and the flying buttress. Gothic architecture is most familiar as the architecture of many of the great cathedrals, abbeys, and churches of Europe.

Renaissance and baroque architecture

[edit]

Renaissance architecture began in the early 14th and lasted until the early 17th century. It demonstrates a conscious revival and development of certain elements of ancient Greek and Roman architectural thought and material culture, particularly the symmetry, proportion, geometry, and the regularity of parts of ancient buildings. Developed first in Florence, with Filippo Brunelleschi as one of its innovators, the Renaissance style quickly spread to other Italian cities. The style was carried to France, Germany, England, Russia, and other parts of Europe at different dates and with varying degrees of impact

Palladian architecture was derived from and inspired by the designs of the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). Palladio's work was strongly based on the symmetry, perspective, and values of the formal classical temple architecture of the Ancient Greeks and Romans. From the 17th century, Palladio's interpretation of this classical architecture was adapted as the style known as Palladianism. It continued to develop until the end of the 18th century, and continued to be popular in Europe throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, where it was frequently employed in the design of public and municipal buildings.

Baroque architecture began in 16th-century Italy. It took the Roman vocabulary of Renaissance architecture and used it in a new rhetorical and theatrical fashion. It was, initially at least, directly linked to the Counter-Reformation, a movement within the Catholic Church to reform itself in response to the Protestant Reformation. Baroque was characterized by new explorations of form, light, and shadow, and a freer treatment of classical elements. It reached its extreme form in the Rococo style.

19th-century architecture

[edit]

Revivalism was a hallmark of nineteenth-century European architecture. Revivals of the Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque styles all took place, alongside revivals of the Classical styles. Regional styles, such as English Tudor, were also revived, as well as non-European styles, such as Chinese (Chinoiserie) and Egyptian. These revivals often used elements of the original style in a freer way than original examples, sometimes borrowing from multiple styles at once. At Alnwick Castle, for example, Gothic revival elements were added to the exterior of the original medieval castle, while the interiors were designed in a Renaissance style.

Art Nouveau architecture was a reaction against the eclectic styles which dominated European architecture in the second half of the 19th century. It was expressed through decoration. The buildings were covered with ornament in curving forms, based on flowers, plants, or animals: butterflies, peacocks, swans, irises, cyclamens, orchids, and water lilies. Façades were asymmetrical, and often decorated with polychrome ceramic tiles. The decoration usually suggested movement; there was no distinction between the structure and the ornament.

20th-century and modern architecture

[edit]Art Deco architecture began in Brussels in 1903–04. Early buildings had clean lines, rectangular forms, and no decoration on the facades; they marked a clean break with the Art Nouveau style. After the First World War, art deco buildings of steel and reinforced concrete began to appear in large cities across Europe and the United States. Buildings became more decorated, and interiors were extremely colorful and dynamic, combining sculpture, murals, and ornate geometric design in marble, glass, ceramics, and stainless steel.

Modernist architecture is a term applied to a group of styles of architecture that emerged in the first half of the 20th century and became dominant after World War II. It was based upon new technologies of construction, particularly the use of glass, steel, and reinforced concrete; and upon a rejection of the traditional neoclassical architecture and Beaux-Arts styles that were popular in the 19th century. Modernist architecture continued to be the dominant architectural style for institutional and corporate buildings into the 1980s, when it was challenged by postmodernism.

Expressionist architecture is a form of modern architecture that began during the first decades of the 20th century, in parallel with the expressionist visual and performing arts that especially developed and dominated in Germany. In the 1950s, the second movement of expressionist architecture developed, initiated by the Ronchamp Chapel Notre-Dame-du-Haut (1950–1955) by Le Corbusier. The style was individualistic, but tendencies include Distortion of form for an emotional effect, efforts at achieving the new, original, and visionary, and a conception of architecture as a work of art.

Postmodern architecture emerged in the 1960s as a reaction against the austerity, formality, and lack of variety of modern architecture, particularly in the international style advocated by Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Embraced in the USA first, it spread to Europe. In contrast to Modernist buildings, Postmodern buildings have curved forms, decorative elements, asymmetry, bright colors, and features often borrowed from earlier periods. Colors and textures unrelated to the structure or function of the building. While rejecting the "puritanism" of modernism, it called for a return to ornament, and an accumulation of citations and collages borrowed from past styles. It borrowed freely from classical architecture, Rococo, neoclassical architecture, the Viennese secession, the British Arts and Crafts movement, the German Jugendstil.

Deconstructivist architecture is a movement of postmodern architecture which appeared in the 1980s, which gives the impression of the fragmentation of the constructed building. It is characterized by an absence of harmony, continuity, or symmetry. Its name comes from the idea of "Deconstruction", a form of semiotic analysis developed by the French philosopher Jacques Derrida. Besides fragmentation, Deconstructivism often manipulates the structure's surface skin and creates by non-rectilinear shapes which appear to distort and dislocate elements of architecture. The finished visual appearance is characterized by unpredictability and controlled chaos.

Literature

[edit]Western literature, also known as European literature,[23] is the literature written in the context of Western culture in the languages of Europe, and is shaped by the periods in which they were conceived, with each period containing prominent western authors, poets, and pieces of literature.

The best of Western literature is considered to be the Western canon. The list of works in the Western canon varies according to the critic's opinions on Western culture and the relative importance of its defining characteristics. Different literary periods held great influence on the literature of Western and European countries, with movements and political changes impacting the prose and poetry of the period. The 16th Century is known for the creation of Renaissance literature,[24] while the 17th century was influenced by both Baroque and Jacobean forms.[25] The 18th century progressed into a period known as the Enlightenment Era for many western countries.[26] This period of military and political advancement influenced the style of literature created by French, Russian and Spanish literary figures.[26] The 19th century was known as the Romantic era, in which the style of writing was influenced by the political issues of the century, and differed from the previous classicist form.[27]

As the Western Roman Empire declined, the Latin tradition was kept alive by writers such as Cassiodorus, Boethius, and Symmachus. The liberal arts flourished at Ravenna under Theodoric, and the Gothic kings surrounded themselves with masters of rhetoric and of grammar. Some lay schools remained in Italy, and noted scholars included Magnus Felix Ennodius, Arator, Venantius Fortunatus, Felix the Grammarian, Peter of Pisa, Paulinus of Aquileia, and many others. The later establishment of the medieval universities of Bologna, Padua, Vicenza, Naples, Salerno, Modena and Parma helped to spread culture and prepared the ground in which the new vernacular literature developed.[28] Classical traditions did not disappear, and affection for the memory of Rome, a preoccupation with politics, and a preference for practice over theory combined to influence the development of Italian literature.[29]

William Shakespeare was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon" (or simply "the Bard"). His extant works, including collaborations, consist of some 39 plays, 154 sonnets, three long narrative poems and a few other verses, some of uncertain authorship. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright. Shakespeare remains arguably the most influential writer in the English language, and his works continue to be studied and reinterpreted.

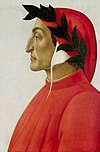

Dante Alighieri, widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian poet, writer, and philosopher.[30] His Divine Comedy, originally called Comedìa (modern Italian: Commedia) and later christened Divina by Giovanni Boccaccio,[31] is widely considered one of the most important poems of the Middle Ages and the greatest literary work in the Italian language.[32] Dante is known for establishing the use of the vernacular in literature at a time when most poetry was written in Latin, which was accessible only to educated readers. His De vulgari eloquentia (On Eloquence in the Vernacular) was one of the first scholarly defenses of the vernacular. His use of the Florentine dialect for works such as The New Life (1295) and Divine Comedy helped establish the modern-day standardized Italian language. His work set a precedent that important Italian writers such as Petrarch and Boccaccio would later follow.

Miguel de Cervantes was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best known for his novel Don Quixote, a work considered as the first modern novel.[33][34][35] The novel has been labelled by many well-known authors as the "best book of all time" and the "best and most central work in world literature".[36][35]

Leo Tolstoy was a Russian writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest and most influential authors of all time.[37][38] He received nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature every year from 1902 to 1906 and for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1901, 1902, and 1909. Tolstoy never having won a Nobel Prize was a major Nobel Prize controversy, and remains one.[39][40]

Film

[edit]Antoine Lumière realized, on 28 December 1895, the first projection, with the Cinematograph, in Paris.[41] In 1897, Georges Méliès established the first cinema studio on a rooftop property in Montreuil, near Paris. Some notable European film movements include German Expressionism, Italian neorealism, French New Wave, Polish Film School, New German Cinema, Portuguese Cinema Novo, Movida Madrileña, Czechoslovak New Wave, Dogme 95, New French Extremity, and Romanian New Wave.

-

Ingmar Bergman, first president of the European Film Academy

The cinema of Europe has its own awards, the European Film Awards. Main festivals : Cannes Film Festival (France), Berlin International Film Festival (Germany). The Venice Film Festival (Italy) or Mostra Internazionale d'Arte Cinematografica di Venezia, is the oldest film festival in the world. Philippe Binant realized, on 2 February 2000, the first digital cinema projection in Europe.[44]

Science

[edit]

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal.[45] Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as alchemy and astrology during the Bronze Age, Iron Age, classical antiquity, and the Middle Ages declined during the early modern period after the establishment of formal disciplines of science in the Age of Enlightenment.

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia around 3000 to 1200 BCE.[46][47] These civilizations' contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine influenced later Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, wherein formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes.[46][47] After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Latin-speaking Western Europe during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of the Middle Ages,[48] but continued to thrive in the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire. Aided by translations of Greek texts, the Hellenistic worldview was preserved and absorbed into the Arabic-speaking Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age.[49] The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived the learning of natural philosophy in the West.[48][50] Traditions of early science were also developed in ancient India and separately in ancient China, the Chinese model having influenced Vietnam, Korea and Japan before Western exploration.[51] Among the Pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica, the Zapotec civilization established their first known traditions of astronomy and mathematics for producing calendars, followed by other civilizations such as the Maya.

Natural philosophy was transformed during the Scientific Revolution in 16th- to 17th-century Europe,[52][53][54] as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions.[55][56][57][58] The New Science that emerged was more mechanistic in its worldview, more integrated with mathematics, and more reliable and open as its knowledge was based on a newly defined scientific method.[56][59][60] More "revolutions" in subsequent centuries soon followed. The chemical revolution of the 18th century, for instance, introduced new quantitative methods and measurements for chemistry.[61] In the 19th century, new perspectives regarding the conservation of energy, age of Earth, and evolution came into focus.[62][63][64][65][66][67] And in the 20th century, new discoveries in genetics and physics laid the foundations for new sub disciplines such as molecular biology and particle physics.[68][69] Moreover, industrial and military concerns as well as the increasing complexity of new research endeavors ushered in the era of "big science," particularly after World War II.[68][69][70]

Philosophy

[edit]

Western philosophy, also known as European philosophy, refers to the philosophical thought, traditions and works of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The word philosophy itself originated from the Ancient Greek philosophía (φιλοσοφία), literally, "the love of wisdom" Ancient Greek: φιλεῖν phileîn, "to love" and σοφία sophía, "wisdom". European philosophy is a predominant strand of philosophy globally, and is central to philosophical enquiry in the Americas and most other parts of the world which have fallen under its influence. The Greek schools of philosophy in antiquity provide the basis of philosophical discourse that extends to today. Christian thought had a huge influence on many fields of European philosophy (as European philosophy has been on Christian thought too), sometimes as a reaction. Many political ideologies were theorized in Europe, such as capitalism, communism, fascism, socialism, or anarchism.

The scope of ancient Western philosophy included the problems of philosophy as they are understood today; but it also included many other disciplines, such as pure mathematics and natural sciences such as physics, astronomy, and biology (Aristotle, for example, wrote on all of these topics). The Classical period of ancient Greek philosophy centers on Socrates and the two generations of students who followed. Medieval philosophy roughly extends from the Christianization of the Roman Empire until the Renaissance.[71] It is defined partly by the rediscovery and further development of classical Greek and Hellenistic philosophy, and partly by the need to address theological problems and to integrate the then-widespread sacred doctrines of Abrahamic religion (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) with secular learning. Some problems discussed throughout this period are the relation of faith to reason, the existence and unity of God, the object of theology and metaphysics, the problems of knowledge, of universals, and of individuation.

The Renaissance ("rebirth") was a period of transition between the Middle Ages and modern thought,[72] in which the recovery of ancient Greek philosophical texts helped shift philosophical interests away from technical studies in logic, metaphysics, and theology towards eclectic inquiries into morality, philology, and mysticism.[73][74] The term "modern philosophy" has multiple usages. For example, Thomas Hobbes is sometimes considered the first modern philosopher because he applied a systematic method to political philosophy.[75][76] By contrast, René Descartes is often considered the first modern philosopher because he grounded his philosophy in problems of knowledge, rather than problems of metaphysics.[77]

German idealism emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s.[78] Transcendental idealism, advocated by Immanuel Kant, is the view that there are limits on what can be understood since there is much that cannot be brought under the conditions of objective judgment. Kant wrote his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) in an attempt to reconcile the conflicting approaches of rationalism and empiricism, and to establish a new groundwork for studying metaphysics. Although Kant held that objective knowledge of the world required the mind to impose a conceptual or categorical framework on the stream of pure sensory data—a framework including space and time themselves—he maintained that things-in-themselves existed independently of human perceptions and judgments; he was therefore not an idealist in any simple sense. Kant's account of things-in-themselves is both controversial and highly complex. Continuing his work, Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Friedrich Schelling dispensed with belief in the independent existence of the world, and created a thoroughgoing idealist philosophy.

The three major contemporary approaches to academic philosophy are analytic philosophy, continental philosophy and pragmatism.[79] They are neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive. The 20th century deals with the upheavals produced by a series of conflicts within philosophical discourse over the basis of knowledge, with classical certainties overthrown, and new social, economic, scientific and logical problems. 20th-century philosophy was set for a series of attempts to reform and preserve and to alter or abolish, older knowledge systems. Seminal figures include Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Religion

[edit]

Christianity has been the dominant religion shaping European culture for at least the last 1700 years.[81][82][83][84][85] Modern philosophical thought has very much been influenced by Christian philosophers such as St Thomas Aquinas and Erasmus. And throughout most of its history, European values have been nearly synonymous with Christian culture.[86] Christian culture is said to have been the predominant force in western civilization, guiding the course of philosophy, art, and science.[87][88] The notion of "Europe and the Western World" has been intimately connected with the concept of "Christianity and Christendom". Many even attribute Christianity for being the link that created a unified European identity.[89]

Religion has been a major influence on the societies, cultures, traditions, philosophies, artistic expressions and laws within present-day Europe. The largest religion in Europe is Christianity.[90] However, irreligion and practical secularisation are also prominent in some countries.[91][92] In Southeastern Europe, three countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and Albania) have Muslim majorities, with Christianity being the second-largest religion in those countries.

Little is known about the prehistoric religion of Neolithic Europe. Bronze and Iron Age religion in Europe as elsewhere was predominantly polytheistic and included Ancient Greek religion, Ancient Roman religion, Slavic paganism, Finnish paganism, Celtic polytheism and Germanic paganism. Modern revival movements of these religions, and religions influenced by them, include Heathenism, Rodnovery, Romuva, Druidry, Wicca.

The Roman Empire officially adopted Christianity in AD 380. Most of Europe underwent Christianisation during the Early Middle Ages, with the process being essentially complete with the Christianisation of Lithuania in the High Middle Ages, with the exception of Al-Andalus. The notion of "Europe" and the "Western World" has been intimately connected with the concept of "Christendom", and many even consider Christianity as the unifying belief that created a European identity,[93] especially since Christianity in the Middle East was marginalized by the rise of Islam from the 8th century. This confrontation led to the Crusades, which ultimately failed militarily, but were an important step in the emergence of a European identity based on religion. Despite this, traditions of folk religion continued at all times, largely independent from institutional religion or dogmatic theology.

The Great Schism of the 11th century and Reformation of the 16th century tore apart Christendom into hostile factions, and following the Age of Enlightenment of the 18th century, atheism and agnosticism have spread across Europe. Nineteenth-century Orientalism contributed to a certain popularity of Hinduism and Buddhism, and the 20th century brought increasing syncretism, New Age, and various new religious movements divorcing spirituality from inherited traditions for many Europeans. Recent times have seen increased secularisation and religious pluralism.[94] Smaller religions include Indian religions, Judaism, and some East Asian religions, which are found in their largest groups in Britain, France, and Kalmykia.

Christianity is the largest religion in Europe, with 76.2% of Europeans considering themselves Christian in 2010,[95] As 2010, Catholics were the largest Christian group in Europe, accounting for more than 48% of European Christians. The second-largest Christian group in Europe was the Orthodox, who made up 32% of European Christians. About 19% of European Christians were part of the Protestant tradition.[95] Russia is the largest Christian country in Europe by population, followed by Germany and Italy.[95] In 2012 Europe constituted in absolute terms the world's largest Christian population.[96] Historically, Europe has been the center and cradle of Christian civilization.[97][98][99][100] Christianity played a prominent role in the development of the European culture and identity.[101][102][103]

According to Scholars, in 2017, Europe's population was 77.8% Christian (up from 74.9% 1970),[104][105] these changes were largely result of the collapse of Communism and switching to Christianity in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc countries.[104]

Cuisine

[edit]The cuisines of European countries are diverse by themselves, although there are common characteristics that distinguish European cooking from cuisines of Asian countries and others.[106][107] Compared with traditional cooking of Asian countries, for example, meat is more prominent and substantial in serving-size. Dairy products are often utilized in the cooking process. Wheat-flour bread has long been the most common source of starch in this cuisine, along with pasta, dumplings, and pastries, although the potato has become a major starch plant in the diet of Europeans and their diaspora since the European colonization of the Americas.

-

Austrian Wienerschnitzel

-

Greek horiatiki salad

-

Polish placki ziemniaczane

-

Finnish Kaalilaatikko

-

Macedonian selsko meso

-

Belarusian garbuzok

-

Bosnian ćevapi

-

German sauerbraten

-

Russian schi

-

Georgian satsivi

-

Montenegrin pržena pastrmka

-

French steak au poivre

-

Slovak kapustnica

-

Latvian pelēkie zirņi ar speķi

-

Bulgarian bob chorba

-

Hungarian chicken paprikash

-

Maltese Stuffat tal-Fenek

-

Swedish gravlax

-

Belgian carbonade flamande

-

British shepherd's pie

-

Romanian ostropel

-

Lithuanian cepelinai

-

Italian bucatini all'amatriciana

-

Italian pizza

-

Italian Pasta alla Norma

-

Italian spaghetti alla carbonara

-

Spanish paella

-

Irish stobhach

-

Albanian fergese

-

Swiss Zürcher Geschnetzeltes

-

Ukrainian paska bread

Fashion

[edit]

The earliest definite examples of needles originate from the Solutrean culture, which existed in France and Spain from 19,000 BC to 15,000 BC. The earliest dyed flax fibers have been found in a cave in Georgia and date back to 36,000 BP. See Clothing in ancient Rome, 1100–1200 in fashion, 1200–1300 in fashion, 1300–1400 in fashion, 1400–1500 in fashion, 1500–1550 in fashion, 1550–1600 in fashion, 1600–1650 in fashion, 1650–1700 in fashion, Textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution. Italian fashion has a long tradition. Top Global Fashion Capital Rankings (2013), by Global Language Monitor, ranked Rome sixth and Milan twelfth.[108] Major Italian fashion labels—such as Gucci, Armani, Prada, Versace, Valentino, Dolce & Gabbana—are among the finest fashion houses in the world. Jewellers such as Bulgari, Damiani, and Buccellati were founded in Italy. The fashion magazine Vogue Italia is one of the most prestigious fashion magazines in the world.[109] Italy is prominent in the field of design, notably interior, architectural, industrial, and urban designs.[110][111] Milan and Turin are the nation's leaders in architectural and industrial design. The city of Milan hosts Fiera Milano, Europe's largest design fair.[112] Milan hosts major design- and architecture-related events and venues, such as the Fuori Salone and the Milan Furniture Fair, and has been home to the designers Bruno Munari, Lucio Fontana, Enrico Castellani, and Piero Manzoni.[113]

Sport

[edit]Olympics

[edit]

Ancient Olympic Games, or the ancient Olympics, were a series of athletic competitions among representatives of city-states and one of the Panhellenic Games of ancient Greece. They were held at the Panhellenic religious sanctuary of Olympia, in honor of Zeus, and the Greeks gave them a mythological origin. The originating Olympic Games are traditionally dated to 776 BC.[114] The games were held every four years, or Olympiad, which became a unit of time in historical chronologies. These Olympiads were referred to based on the winner of their stadion sprint, e.g., "the third year of the eighteenth Olympiad when Ladas of Argos won the stadion".[115] They continued to be celebrated when Greece came under Roman rule in the 2nd century BC. Their last recorded celebration was in AD 393, under the emperor Theodosius I, but archaeological evidence indicates that some games were still held after this date.[116][117] The games likely came to an end under Theodosius II, possibly in connection with a fire that burned down the temple of the Olympian Zeus during his reign.[118]

During the celebration of the games, the Olympic truce (ekecheiría) was announced so that athletes and religious pilgrims could travel from their cities to the games in safety. The prizes for the victors were olive leaf wreaths or crowns. The games became a political tool used by city-states to assert dominance over their rival city states. Politicians would announce political alliances at the games, and in times of war, priests would offer sacrifices to the gods for victory. The games were also used to help spread Hellenistic culture throughout the Mediterranean. The Olympics also featured religious celebrations. The statue of Zeus at Olympia was counted as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Sculptors and poets would congregate each Olympiad to display their works of art to would-be patrons.

The ancient Olympics had fewer events than the modern games, and for many years only freeborn Greek men were allowed to participate,[119] although there were victorious women chariot owners. Moreover, throughout their history, the Olympics, both ancient and modern, have occasionally become arenas where political expressions, such as demonstrations, boycotts, and embargoes, have been employed by nations and individuals to exert influence over these sporting events.[120] As long as they met the entrance criteria, athletes from any Greek city-state and kingdom were allowed to participate. The games were always held at Olympia rather than moving between different locations like the modern Olympic Games.[121] Victors at the Olympics were honored, and their feats chronicled for future generations.

The modern Olympic Games are the world's leading international sporting events. They feature summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a variety of competitions. The Olympic Games are considered the world's foremost sports competition, with more than 200 teams, representing sovereign states and territories, participating. By default, the Games generally substitute for any world championships during the year in which they take place (however, each class usually maintains its own records).[122] The Olympics are staged every four years. Since 1994, they have alternated between the Summer and Winter Olympics every two years during the four-year Olympiad.[123][124]

Their creation was inspired by the ancient Olympic Games, held in Olympia, Greece, from the 8th century BC to the 4th century AD. Baron Pierre de Coubertin founded the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1894, leading to the first modern Games in Athens in 1896. The IOC is the governing body of the Olympic Movement, which encompasses all entities and individuals involved in the Olympic Games. The Olympic Charter defines their structure and authority.

The evolution of the Olympic Movement during the 20th and 21st centuries has resulted in numerous changes to the Olympic Games. Some of these adjustments include the creation of the Winter Olympic Games for snow and ice sports, the Paralympic Games for athletes with disabilities, the Youth Olympic Games for athletes aged 14 to 18, the five Continental Games (Pan American, African, Asian, European, and Pacific), and the World Games for sports that are not contested in the Olympic Games. The IOC also endorses the Deaflympics and the Special Olympics. The IOC need to adapt to a variety of economic, political, and technological advancements. The abuse of amateur rules prompted the IOC to shift away from pure amateurism, as envisioned by Coubertin, to the acceptance of professional athletes participating at the Games. The growing importance of mass media has created the issue of corporate sponsorship and general commercialisation of the Games. World Wars I and II led to the cancellation of the 1916, 1940, and 1944 Olympics; large-scale boycotts during the Cold War limited participation in the 1980 and 1984 Olympics;[125] and the 2020 Olympics were postponed until 2021 because of the COVID-19 restrictions.

Contemporary sports

[edit]

- Association football, which has its origins in the United Kingdom. The oldest association is The Football Association of England (1863), and the first international match was between Scotland and England (1872). It is now the world's most popular sport and is played throughout Europe.

- Cricket has its origins in southeast England. It is popular throughout England and Wales, and parts of the Netherlands. It is also popular in other areas in Northwest Europe. It is however, very popular worldwide, especially in Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and the Indian subcontinent.

- Cycling, which is also immensely popular as a means of transport, has most of its sporting adherents in Europe. Tour de France is the world's most-watched live annual sporting event. The bicycle itself is probably from France (see History of the bicycle).

- The discus throw, javelin throw, and shot put have their origins in ancient Greece. The Olympics, both ancient and modern, have their origins too in Europe, and have a massive influence globally.

- Field Hockey, as a modern game, began in 18th century England, with Ireland having the oldest federation. It is popular in Western Europe, the Indian subcontinent, Australia and East Asia. Ice hockey, popular in Europe and North America, may derive from this sport.

- Golf, one of the most popular sports in Europe, Asia, and North America, has its origins in Scotland, with the oldest course being at Musselburgh.

- Handball, which is popular in Europe and elsewhere, has its origins in antiquity. The modern game is from Denmark and Germany, with Germany having been involved in both the first women's and men's internationals.

- Rugby League and Rugby Union were both created in England. They both have similar origins to football. Rugby Union is the older of the two codes and has rules that date from 1845 (see articles: History of rugby league and History of rugby union). They acrimoniously split in the late 19th century over the treatment of injured players. Rugby league gradually changed its laws over the next century with the result that today both sports have little in common, apart from the basics. They have both been carried abroad by colonization, particularly to many former British colonies. American Football and Canadian Football are derivatives of rugby.

- Tennis which originates from England, and related games such as Table Tennis, derive from the game Real Tennis which is from France. It is popular throughout the world.

Regional sports

[edit]

In addition, Europe has numerous national or regional sports which do not command a large international following outside of emigrant groups. These include:

- Alpine Wrestling in Switzerland.

- Bandy in Russia, Sweden, and Finland

- Basque Pelota in parts of Spain and France, and which has been brought to the Americas by emigrants.

- Bullfighting in Spain, Portugal, and parts of southern France near the Spanish Border.

- Gaelic Football in Ireland, which influenced Australian rules football.

- Gaelic Handball (Ireland) which was taken to the United States in the form of American Handball.

- Hurling in Ireland.

- Korfbal in the Netherlands and Belgium.

- Pesäpallo (Boboll) in Finland

- Pétanque, Boules, Irish Road Bowling, Skittles, Bocce, and Bowls and others are variations of bowling games which are popular throughout Europe and have been spread around the world.

- Rounders from England[126][127] now popular in northwest Europe from which Baseball derives.

- Shinty in Scotland, which influenced ice hockey in Canada (see also Shinny).

- Trotting in southern Europe.

Some sports competitions feature a European team gathering athletes from different European countries. These teams use the European flag as an emblem. The most famous of these competitions is the Ryder Cup in golf. Some sporting organizations hold European Championships like European Cricket Council, the European Games, the European Rugby Cup (Club/Regional competition), the European SC Championships, the FIRA - Association of European Rugby, the IIHF, the Mitropa Cup, the Rugby League European Federation - European Championship, the Sport in the European Union and the UEFA.

European politics

[edit]

Overview

[edit]See: History of Europe

European Union

[edit]See: Politics of the European Union

Capital of Culture

[edit]Each year since 1985 one or more cities across Europe are chosen as European Capital of Culture, an EU initiative. Here are the past and future capitals:

- 1985: Athens

- 1986: Florence

- 1987: Amsterdam

- 1988: Berlin

- 1989: Paris

- 1990: Glasgow

- 1991: Dublin

- 1992: Madrid

- 1993: Antwerp

- 1994: Lisbon

- 1995: Luxembourg

- 1996: Copenhagen

- 1997: Thessaloniki

- 1998: Stockholm

- 1999: Weimar

- 2000: Avignon, Bergen, Bologna, Brussels, Helsinki, Kraków, Prague, Reykjavík, Santiago de Compostela

- 2001: Rotterdam, Porto

- 2002: Bruges, Salamanca

- 2003: Graz

- 2004: Genoa, Lille

- 2005: Cork

- 2006: Patras

- 2007: Sibiu, Luxembourg, Greater Region

- 2008: Liverpool, Stavanger

- 2009: Vilnius, Linz

- 2010: Essen (representing the Ruhr), Istanbul, Pécs

- 2011: Turku, Tallinn

- 2012: Guimarães, Maribor

- 2013: Marseille, Košice

- 2014: Umeå, Riga

- 2015: Mons, Plzeň

- 2016: San Sebastián, Wrocław

- 2017: Aarhus, Paphos

- 2018: Valletta, Malta and Leeuwarden

- 2019: Plovdiv and Matera

- 2020: Galway and Rijeka

Symbols

[edit]

A number of symbols of Europe have emerged since antiquity, notably the mythological figure of Europa. Several symbols were introduced in the 1950s and 1960s by the European Council. The European Communities created additional symbols for itself in 1985, which was to become inherited by the European Union (EU) in 1993. Such symbols of the European Union now represent political positions in support of EU policies and European integration as advocated by Europeans.

Europa was used as a geographical term, for one of the great divisions of the known world, by Herodotus (in a reduced geographical scope, referring to parts of Thrace or Epirus, also in the Homeric hymn to Apollo). It became the geographical term for the landmass west of the Tanais in the Roman-era geography by Strabo and Ptolemy. Europa first began to be used in a cultural sense, denoting the territory of Latin Christendom, in the Carolingian period. Europa is a feminine name, the name of a nymph in Hesiod, and in a legend first related by Herodotus, the name of a Phoenician noble-woman abducted by Greeks (in Herodotus' opinion, Cretans). The classical legend of Europa being abducted not by Greek pirates but by Zeus in the shape of a bull is told in Ovid's Metamorphoses. According to the account, Zeus took the guise of a tame white bull and mixed himself with the herds of Europa's father. While Europa and her female attendants were gathering flowers, she saw the bull, and got onto his back. Zeus took that opportunity and ran to the sea and swam, with her on his back, to the island of Crete. There he revealed his true identity, and Europa became the first queen of Crete. Zeus gave her a necklace made by Hephaestus and three additional gifts: Talos, Laelaps and a javelin that never missed. Zeus later re-created the shape of the white bull in the stars, which is now known as the constellation Taurus.

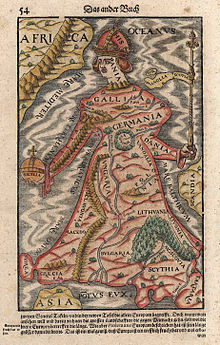

Europa regina (Latin for Queen Europe) is the cartographic depiction of the European continent as a queen.[128][129] Introduced and made popular during the mannerist period, Europa Regina is the map-like depiction of the European continent as a queen.[128][129] Made popular in the 16th century, the map shows Europe as a young and graceful woman wearing imperial regalia. The Iberian Peninsula (Hispania) is the head, wearing a crown shaped like the Carolingian hoop crown. The Pyrenees, forming the neck, separate the Iberian Peninsula from France (Gallia), which makes up the upper chest. The Holy Roman Empire (Germania and other territories) is the centre of the torso, with Bohemia (sometimes Austria in early depictions) being the heart of the woman (alternatively described as a medallion at her waist). Her long gown stretches to Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, Livonia, Bulgaria, Muscovy, Macedonia and Greece. In her arms, formed by Italy and Denmark, she holds a sceptre and an orb (Sicily).[130] In most depictions, Africa, Asia and the Scandinavian peninsula are partially shown,[130] as are the British Isles, in schematic form.[130]

Charlemagne (Latin: Carolus Magnus; King of the Franks from 768; Holy Roman Emperor c. 742 – 814), also known as Charles the Great, is considered the founder of the French and German monarchies. Known as Pater Europae («Father of Europe»),[131][132] he established an empire that represented the most expansive European unification since the fall of the Western Roman Empire and brought about a renaissance that formed a pan-European identity whilst marking the end of Late Antiquity.[131][133] There was also a contemporary intellectual and cultural revival which profoundly marked the history of Western Europe. This gave Charlemagne a legendary standing that transcended his military accomplishments.[131][134][135]

The Roman Catholic Church venerates six saints as "patrons of Europe". Benedict of Nursia had been declared "Patron saint of all Europe" by Pope Paul VI in 1964.[136] Pope John Paul II named between 1980 and 1999 Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Bridget of Sweden, Catherine of Siena and Teresa Benedicta of the Cross as co-patrons.[137][138]

A flag of Europe was introduced by the Council of Europe in 1955, originally intended as a "symbol for the whole of Europe",[139] but due to its adoption by the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1985, and hence by the European Union (EU) as the successor organisation of the EEC, the flag is now strongly associated with the European Union so that it no longer serves the function of representing "Europe as a whole" at least since the early 2000s. The flag has notably been used by pro-EU protestors in the colour revolutions of the 2000s, e.g., in Belarus in 2004[140] by the pro-EU faction in the Euromaidan riots in Ukraine in 2013, and by the pro-EU faction in the Brexit campaigns of 2016.

See also

[edit]- Compendium of cultural policies and trends in Europe

- Cultural policies of the European Union

- Europalia

- European dances

- European Heritage Day

- Europeanisation

- Romano-Germanic culture

- Western culture

- Westernization

References

[edit]- ^ Mason, D. (2015). A Concise History of Modern Europe: Liberty, Equality, Solidarity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 2.

- ^ Cederman (2001:2) remarks: "Given the absence of an explicit legal definition and the plethora of competing identities, it is indeed hard to avoid the conclusion that Europe is an essentially contested concept." Cf. also Davies (1996:15); Berting (2006:51).

- ^ Cf. Jordan-Bychkov (2008:13), Davies (1996:15), Berting (2006:51-56).

- ^ a b K. Bochmann (1990) L'idée d'Europe jusqu'au XXè siècle, quoted in Berting (2006:52). Cf. Davies (1996:15): "No two lists of the main constituents of European civilization would ever coincide. But many items have always featured prominently: from the roots of the Christian world in Greece, Rome and Judaism to modern phenomena such as the Enlightenment, modernization, romanticism, nationalism, liberalism, imperialism, totalitarianism."

- ^ a b c d e Berting 2006, p. 52

- ^ Berting 2006, p. 51

- ^ Duran (1995:81)

- ^ "EliotPassages". www3.dbu.edu.

- ^ Pagden, Anthony (2008). Worlds at War The 2,500-Year Struggle Between East and West. Oxford University Press. pp. xi. ISBN 9780199237432.

The awareness that East and West were not only different regions of the world but also regions filled with different peoples, with different cultures, worshipping different gods and, most crucially, holding different views on how best to live their lives, we owe not to an Asian but to a Western people: the Greeks. It was a Greek historian, Herodotus, writing in the fifth century B.C.E., who first stopped to ask what it was that divided Europe and Asia [...] This East as Herodotus knew it, the lands that lay between the European peninsula and the Ganges

- ^ Shvili, Jason (26 April 2021). "The Western World". worldatlas.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022.

The concept of the Western world, as opposed to other parts of the world, was born in ancient Greece, specifically in the years 480-479 BCE, when the ancient Greek city states fought against the powerful Persian Empire to the east.

- ^ Hunt, Lynn; Martin, Thomas R.; Rosenwein, Barbara H.; Smith, Bonnie G. (2015). The Making of the West: People and Cultures. Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 4. ISBN 978-1457681523.

Building on concepts from the Near East, Greeks originated the idea of the West as a separate region, identifying Europe as the West (where the sun sets) and different from the East (where the sun rises).

- ^ Sanjay Kumar (2021). A Handbook of Political Geography. K.K. Publications. pp. 125–127.

- ^ Paolucci, Antonio (2004). Bracci, Susanna; Falletti, Franca; Matteini, Mauro (eds.). Exploring David: Diagnostic Tests and State of Conservation. Giunti Editore. p. 12. ISBN 978-88-09-03325-2.

The David in Florence's Accademia is young Michelangelo's masterpiece.

- ^ Buonarroti, Michelangelo; Paolucci, Antonio (2006). Michelangelo's David. Harry N. Abrams. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-903973-99-8.

...a masterpiece of throbbing vitality.

- ^ "The Theft That Made Mona Lisa a Masterpiece". All Things Considered. 30 July 2011. NPR. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ Sassoon, Donald (21 September 2001). "Why I think Mona Lisa became an icon". Times Higher Education.

- ^ Carrier, David (2006). Museum Skepticism: A History of the Display of Art in Public Galleries. Duke University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8223-3694-5.

- ^ Erlich, Cyril (1990). The Piano: A History. Oxford University Press, US; Revised edition. ISBN 978-0-1981-6171-4.; Allen, Edward Heron (1914). Violin-making, as it was and is: Being a Historical, Theoretical, and Practical Treatise on the Science and Art of Violin-making, for the Use of Violin Makers and Players, Amateur and Professional. Preceded by An Essay on the Violin and Its Position as a Musical Instrument. E. Howe. Accessed 5 September 2015.

- ^ The Medieval Winter Fairytale of Tallinn – Journey Wonders

- ^ The Many Faces Of Architecture Of Tallinn – Visit Tallinn

- ^ Tallinn – European Capital of Culture 2011 application – Tallinn.ee

- ^ "Leo Tolstoy | Biography, Books, Religion, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-10-11.

- ^ "Western literature". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ Bates, Catherine (2019). "Recent Studies in the English Renaissance". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 59 (1): 203–241. doi:10.1353/sel.2019.0009. ISSN 1522-9270. S2CID 150751824.

- ^ Brownlee, Victoria (2018). Biblical readings and literary writings in early modern England, 1558–1625. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-881248-7. OCLC 1002113576.

- ^ a b Zorin, Andrei (1998). "Faced with a Difficult Test". Russian Studies in Literature. 35: 28–30. doi:10.2753/RSL1061-1975350128 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ^ Betti, Franco (1997). "Key Aspects of Romantic Poetics in Italian Literature". Italica. 74 (2): 185–200. doi:10.2307/480076. ISSN 0021-3020. JSTOR 480076.

- ^ "Duecento e Trecento, lingua del" (in Italian). Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bartoli, Adolfo; Oelsner, Hermann (1911). "Italian Literature". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 898.

- ^ Wetherbee, Winthrop; Aleksander, Jason (April 30, 2018). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Hutton, Edward (1910). Giovanni Boccaccio, a Biographical Study Archived February 4, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. p. 273.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (1994). The Western Canon. Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781573225144.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (13 December 2003). "The knight in the mirror". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ Puchau de Lecea, Ana; Pérez de León, Vicente (25 June 2018). "Guide to the classics: Don Quixote, the world's first modern novel – and one of the best". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Don Quixote gets authors' votes". BBC News. 7 May 2002. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ Chrisafis, Angelique (21 July 2003). "Don Quixote is the world's best book say the world's top authors". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ Burt, Daniel S. (2009). The Literary 100, Revised Edition: A Ranking of the Most Influential Novelists, Playwrights, and Poets of All Time. Facts On File. pp. 13–16.

- ^ Popova, Maria (2012-01-30). "The Greatest Books of All Time, as Voted by 125 Famous Authors". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 2023-12-28.

- ^ Hedin, Naboth (1950-10-01). "Winning the Nobel Prize". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 2023-12-28.

- ^ Lichtman, Marshall A. (2022-07-31). "Controversies in Selecting Nobel Laureates: An Historical Commentary". Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal. 13 (3): e0022. doi:10.5041/RMMJ.10479. ISSN 2076-9172. PMC 9345763. PMID 35921488.

- ^ Universalis, Encyclopædia. "PRÉSENTATION DU CINÉMATOGRAPHE LUMIÈRE". Encyclopædia Universalis.

- ^ Avedon, Richard (14 April 2007). "The top 21 British directors of all time". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

Unquestionably the greatest filmmaker to emerge from these islands, Hitchcock did more than any director to shape modern cinema, which would be utterly different without him. His flair was for narrative, cruelly withholding crucial information (from his characters and from the audience) and engaging the emotions of the audience like no one else.

- ^ "Cinecittà, c'è l'accordo per espandere gli Studios italiani" (in Italian). 30 December 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ Cahiers du cinéma, n°hors-série, Paris, April 2000, p. 32 (cf. also Histoire des communications, 2011, p. 10. Archived 19 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Cohen, Eliel (2021). "The boundary lens: theorising academic activity". The University and its Boundaries (1st ed.). New York, New York: Routledge. pp. 14–41. ISBN 978-0367562984. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b Lindberg, David C. (2007). "Science before the Greeks". The Beginnings of Western Science (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ a b Grant, Edward (2007). "Ancient Egypt to Plato". A History of Natural Philosophy. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-052-1-68957-1.

- ^ a b Lindberg, David C. (2007). "The revival of learning in the West". The Beginnings of Western Science (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 193–224. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). "Islamic science". The Beginnings of Western Science (Second ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 163–92. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (2007). "The recovery and assimilation of Greek and Islamic science". The Beginnings of Western Science (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 225–253. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Shigeru, Nakayama (1995). "History of East Asian Science: Needs and Opportunities". Osiris. 10: 80–94. doi:10.1086/368744. JSTOR 301914. S2CID 224789083. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ Küskü, Elif Aslan (2022-01-01). "Examination of Scientific Revolution Medicine on the Human Body / Bilimsel Devrim Tıbbını İnsan Bedeni Üzerinden İncelemek". The Legends: Journal of European History Studies. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Hendrix, Scott E. (2011). "Natural Philosophy or Science in Premodern Epistemic Regimes? The Case of the Astrology of Albert the Great and Galileo Galilei". Teorie Vědy / Theory of Science. 33 (1): 111–132. doi:10.46938/tv.2011.72. S2CID 258069710. Archived from the original on 18 November 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ Principe, Lawrence M. (2011). "Introduction". Scientific Revolution: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-199-56741-6.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (1990). "Conceptions of the Scientific Revolution from Baker to Butterfield: A preliminary sketch". In Lindberg, David C.; Westman, Robert S. (eds.). Reappraisals of the Scientific Revolution (First ed.). Chicago: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-521-34262-9.

- ^ a b Lindberg, David C. (2007). "The legacy of ancient and medieval science". The Beginnings of Western Science (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 357–368. ISBN 978-0-226-48205-7.

- ^ Del Soldato, Eva (2016). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2016 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ^ Grant, Edward (2007). "Transformation of medieval natural philosophy from the early period modern period to the end of the nineteenth century". A History of Natural Philosophy. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 274–322. ISBN 978-052-1-68957-1.

- ^ Gal, Ofer (2021). "The New Science". The Origins of Modern Science. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 308–349. ISBN 978-1316649701.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J.; Morus, Iwan Rhys (2020). "The scientific revolution". Making Modern Science (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 25–57. ISBN 978-0226365763.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J.; Morus, Iwan Rhys (2020). "The chemical revolution". Making Modern Science (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 58–82. ISBN 978-0226365763.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J.; Morus, Iwan Rhys (2020). "The conservation of energy". Making Modern Science (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 83–107. ISBN 978-0226365763.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J.; Morus, Iwan Rhys (2020). "The age of the earth". Making Modern Science (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 108–133. ISBN 978-0226365763.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J.; Morus, Iwan Rhys (2020). "The Darwinian revolution". Making Modern Science (2nd ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 134–171. ISBN 978-0226365763.

- ^ Cahan, David, ed. (2003). From Natural Philosophy to the Sciences: Writing the History of Nineteenth-Century Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-08928-7.

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary dates the origin of the word "scientist" to 1834.

- ^ Lightman, Bernard (2011). "Science and the Public". In Shank, Michael; Numbers, Ronald; Harrison, Peter (eds.). Wrestling with Nature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-226-31783-0.

- ^ a b Bowler, Peter J.; Morus, Iwan Rhys (2020). "Genetics". Making Modern Science (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 197–221. ISBN 978-0226365763.

- ^ a b Bowler, Peter J.; Morus, Iwan Rhys (2020). "Twentieth-century physics". Making Modern Science (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 262–285. ISBN 978-0226365763.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J.; Morus, Iwan Rhys (2020). "Introduction: Science, society, and history". Making Modern Science (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-0226365763.

- ^ Frederick Copleston, A History of Philosophy, Volume II: From Augustine to Scotus (Burns & Oates, 1950), p. 1, dates medieval philosophy proper from the Carolingian Renaissance in the eighth century to the end of the fourteenth century, though he includes Augustine and the Patristic fathers as precursors. Desmond Henry, in Edwards 1967, pp. 252–257 volume 5, starts with Augustine and ends with Nicholas of Oresme in the late fourteenth century. David Luscombe, Medieval Thought (Oxford University Press, 1997), dates medieval philosophy from the conversion of Constantine in 312 to the Protestant Reformation in the 1520s. Christopher Hughes, in A.C. Grayling (ed.), Philosophy 2: Further through the Subject (Oxford University Press, 1998), covers philosophers from Augustine to Ockham. Gracia 2008, p. 620 identifies medieval philosophy as running from Augustine to John of St. Thomas in the seventeenth century. Kenny 2012, volume II begins with Augustine and ends with the Lateran Council of 1512.